Deciphering Sake Labels

“Hey, I’ve found this beautiful bottle of sake. It tastes amazing! It’s called… ehm, it’s a….?” 😕

Deciphering sake labels can be difficult, all the more so if you don’t know any Japanese (and even then, the artistic calligraphy can complicate things). Luckily, many importers will add their own back label to the sake they sell. But if you have bottle without such information, this article will help you out.

First things first

The first thing you will want to find out is probably what category of sake you’re looking at. Is it a fruity ginjo or a plain fustushu (regular sake)? Luckily, this information usually will be presented quite prominently on the front label. Let’s have a look at a typical example.

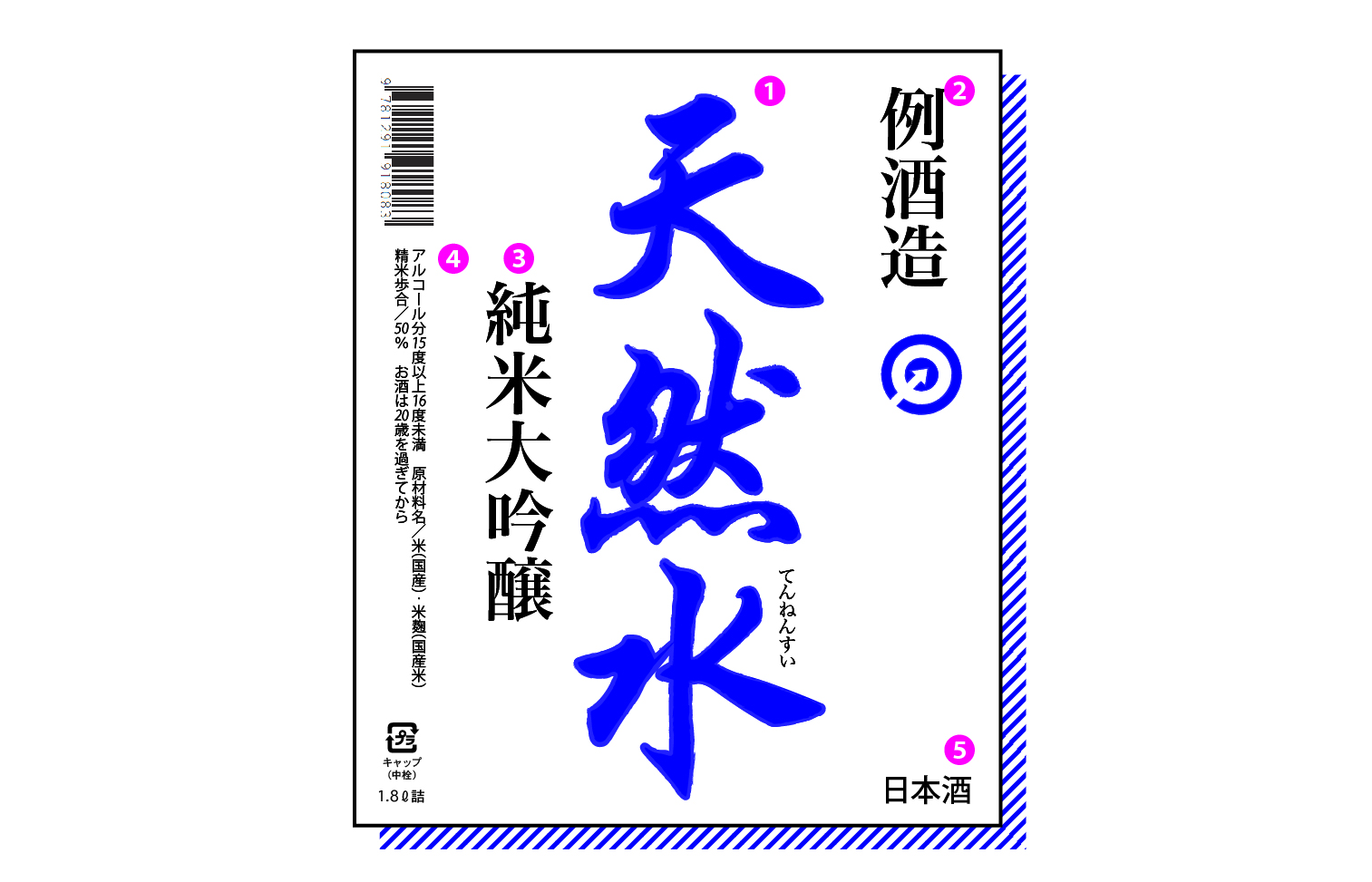

(click image to enlarge) ➊Brand name, ➋Brewery name ➌Category (Here: Junmai Dai-ginjo), ➍alcohol content, ingredients, legal information ➎’Japanese Sake’

The largest item on the front label is usually the ➀ brand name. Because the calligraphy can be difficult to read and the name might contain uncommon characters, it is often repeated in smaller print in kana (syllabic characters) or Latin letter; a few might even have a translated brand name in English.

The ➁ brewery name is often less well-known than the brand name. It might not even be as prominently displayed as it is in this example, but the name and address of need to be somewhere on the front or back label. A brewery might only produce one brand or they can have a range of products with different brand names and profiles.

This is the important part, the ➂ category. In this case, our example is a junmai dai-ginjo, i.e. a sake made from highly polished rice and without added alcohol. See our article on the main types of sake for more info. Below is a list of the different grades as they would be written with Japanese characters:

Premium sake is classified by rice polishing ratio. (Click to enlarge)

普通酒 — Futsu-shu, ‘regular’ or ‘table sake’.

本醸造 — Honjozo, made with the addition of alcohol

純米 — Junmai, made without added alcohol. can also be used in combination with any of the following categories.

吟醸 — Ginjo, ‘careful brewing’ using highly polished rice

大吟醸 — Dai-ginjo, ‘very careful brewing’ using very highly polished rice (min. 50% polishing rate)

Ordinary futsu-shu will often not be labelled as such but just say nihonshu (日本酒) or seishu (清酒) on the label! If there is no mention of a category at all, you can assume that the sake is a Futsu-shu.

If you can’t decipher the characters on the front label, have a look at the back label, where this information might be repeated in a more legible typeface, or try to get some information from the polishing rate and ingredients.

Then, there is the ➃ alcohol content, polishing ratio and list of ingredients. Both are required by law. The alcohol content will often be written as a range: in this example, ‘over 15%, but below 16%’, i.e. 15.0–15.9%. This is done to account for naturally occurring variation between batches, although brewers adjust and balance the alcohol content by adding a little water before bottling. Look for アルコール

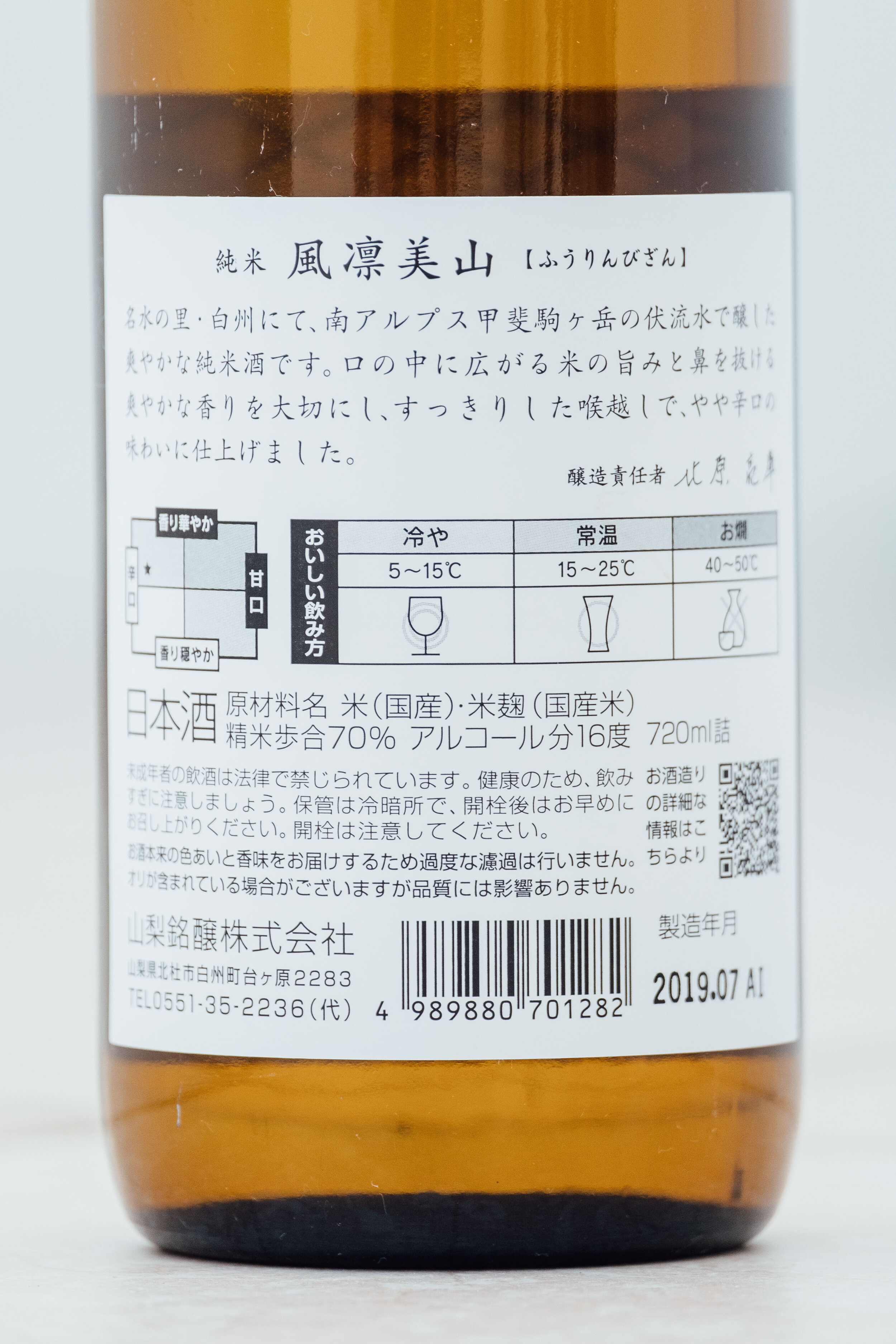

If you know where to look, it’s all there. Ingredients: Rice, Koji, Alcohol. Rice polishing rate: 70%, Alcohol 15%.

The list of ingredients is usually quite short: it can be two ingredients or three. A junmai sake (sake without added alcohol) will only have rice and rice koji listed here. Any other sake will contain rice, rice koji, and alcohol. Alcohol in this case is always written with the syllabic characters used for foreign words (called katakana), which look very different and are easy to spot even if you cannot read Japanese: アルコール.

The brewery can chose to give you some extra information like the origin and variety of rice, yeast strain, and how much koji rice was used (given as a percentage).

For any premium sake, the rice polishing rate also has to be mentioned. The Japanese term to look for is 精米歩合.

Our example also has a friendly reminder that you need to be of legal drinking age (20 in Japan) to enjoy sake. Again, this is a legal requirement.

Last, it needs to be clear that what you’re holding in your hand is actually sake. The label needs to say ➄ 日本酒(‘nihon-shu,’ Japanese Sake) or 清酒(‘seishu,’ clear sake).

Back Labels

The brand name and category will usually be featured very prominently on the front label. But a lot of the other information can be on the back instead. Many breweries nowadays try to make it easier for the consumer to find a sake that meets their expectations, so the back label often holds a lot of valuable information.

Some will have small charts that give you an indication of dryness and optimal serving temperature. Below are two typical examples.

These two graphs give an indication of sweetness/dryness and intensity. This sake is on the dry side and fairly light.

This table indicates the recommended serving temperature. In this case ‘chilled’ is the best option.

Tanrei, or tanrei-karakuchi (淡麗辛口) is used to describe a style of sake popular in Niigata Prefecture that is light, dry and has a clean, short finish.

The graph on the left shows you, how sweet (甘) or dry (辛) the sake is. in this case, it’s fairly dry. The line below indicates the intensity of taste and body with tanrei (淡麗), a Japanese term for ‘light and refreshing’, on the left and ‘rich and strong’ (濃醇) on the right.

This daiginjo is very light (淡麗) and perfectly balanced between dryness and sweetness. It is best enjoyed chilled (冷).

If there is no such graph, try to find a number with a plus or minus in front of it, the ‘Sake Meter Value’ (SMV) or Nihonshu-do [日本酒度]. This value can be used as an indicator of sweetness: the higher the number the dryer the sake will be (-3 would be very sweet, +10 very dry). It is calculated from the specific gravity of the sake, which is influenced by sugar and alcohol content. As the perception of sweetness depends on many factors, SMV might not always accurately reflect the taste, but especially at its extremes it is a good guide.

This sake should be enjoyed in a wine glass at 5–15ºC.

Serving temperature is often displayed as a table like in the example on the right. The labels are: ‘on the rocks’ (ロック), chilled (5–10ºC), room temperature (like for wine, actually around 15–18ºC), warm (45–50ºC), and hot (50–55ºC). The indicators used here are common in Japan in any context. A double circle ◎ marks the best option, followed by a simple circle ◯. The triangle △ means ‘ok, but not recommended’. A cross × would be a definite ‘no’.

As mentioned, many producers list the ingredients on the back label instead of the front. Some also give you more geeky information, like what rice variety and which yeast has been used, how much of the total rice volume was koji, or even information about the amount of amino acids.

We will cover the different rice varieties used for sake brewing in more detail in another article and also yeast deserves more attention as a topic of its own as it greatly influences the aroma.

Shipping date

One thing to look out for when buying sake outside of Japan is the age of the bottle. Your local shop might not sell a very high volume of sake or a bottle could have been forgotten in the back of the shelf. Most sake is meant to be consumed within a year of its release and will deteriorate in quality if it is not stored correctly. So it’s good to know when it was actually produced and shipped from the brewery!

This example shows both the production date (製造年月) —in this case actually the bottling date(瓶詰年月)— and the shipping date (出荷年月) below. This particular sake was brewed in December 2018 and then stored at the brewery until January 2020.

See also: What does BY stand for?

Breweries are required by law to show the shipping date (出荷年月) on the label. This is the month and year when the bottle left the brewery’s warehouse. Some breweries might also show the production or bottling date, but if there’s only one number, it’s safe to assume that this is the shipping date. This is usually printed as YY.MM. The first number is the year, followed by the month, using the western/Gregorian calendar.

If the bottle has a shipping date that is more than one year in the past, you should be very careful, especially if you’re looking at a delicate ginjo-type sake or if the bottle has not been kept refrigerated.

Some Useful Kanji

Kanji are adopted Chinese characters used in Japanese writing. You might not want to study all of these, but even just knowing a few simple characters will make it much easier to identify a sake you like. Especially the characters for ginjo 吟醸 (just memorise the first one) and rice 米 will come handy and can help you make an educated guess about the type of sake.

大—Big, great

As in 大吟醸 dai-ginjo.

火—Fire

火入 (hi-ire) means pasteurised. Some brands offer the same sake in pasteurised and unpasteurised (nama) versions, so be careful to pick the right one.

中—Middle

If you have an especially high-quality sake that was bottled only from the middle part of the pressing it will be labelled as 中取り (naka-dori). These sakes are characterised by balance and smoothness and usually of the dai-ginjo category.

山—Mountain

山廃 yamahai or 山廃仕込み yamahai-shikomi is an old brewing technique that results in a richer, full-bodied sake with relatively high acidity and complex, slightly funky aroma.

田—Rice field

Together with the previous kanji for mountain, this might help you identify one of the most-used rice varieties for premium sake: Yamada-Nishiki 山田錦.

古—Old

Koshu 古酒 is sake that has been aged for several years. This is a specialty style and might not be to everybody’s taste.

生—Living

If you see this character by itself or as 生酒 (nama-zake) you have an unpasteurised sake in you hands (remember to keep it cold!). Many unpasteurised sakes will have a sticker with this character on the neck of the bottle.

But the same character is also used in the term 生酛 kimoto (‘living yeast starter’), for the old brewing method that creates a more umami-rich, high-acid and full-bodied sake.

米 — Rice

This one will appear a lot, and luckily its symmetrical shape makes it easy to remember. Look for 純米 (junmai).

甘—Sweet

This one explains itself. Don’t get the character confused with any of the following: 日白百目自月 😉

辛—Dry, spicy

Very dry sakes are usually not shy about it and will say so on the label. Look for 辛口 (karakuchi, ‘dry taste’).

冷—Cool

This can come up in the table of recommended serving temperature or to warn you that the bottle should be kept refrigerated. The latter is written as 要冷蔵 (image on the left).

酒 — Alcohol, sake

Imagine a full barrel of sake that splashes over as the lid is put on. This will most likely appear as 日本酒 (nihonshu, Japanese sake) or 清酒 (seishu, clear sake).

歩合 — Ratio, percentage

The little ‘house’ is easy to spot. Used in 精米歩合 — rice polishing ratio.

吟醸—Ginjo

Yes, the last character is a mess of lines to the untrained eye, but try to remember the first one (square, triangle, 7), because this one is pretty useful.